24.07.2018 | Biodiversity Conservation, Media Release, TOP NEWS

Leipzig/Halle. Great opportunity for European brown bears: a new study spearheaded by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) shows that there are still many areas in Europe where bears are extinct but with suitable habitat for hosting the species. An effective management of the species, including a reduction of direct pressures by humans (like hunting), has the potential to help these animals come back in many of these areas, according to the head of the study. It is now important to plan the recovery of the species while taking measures to prevent conflicts.

Close-up view of the two cubs.

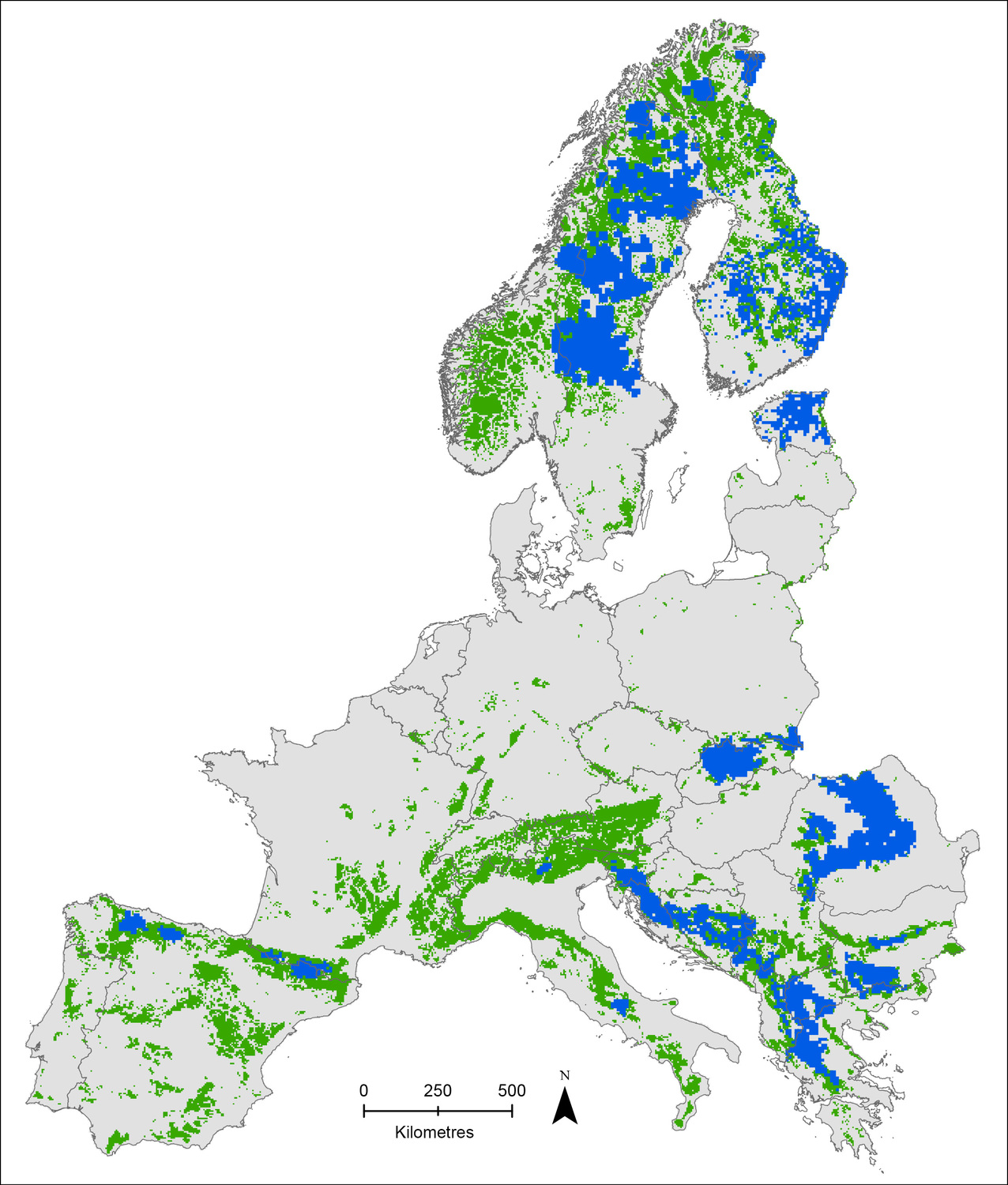

The map of Europe shows areas currently inhabited by brown bears (blue), areas that are suitable habitat for bears according to the new study, but which are currently not populated (green) and areas unsuitable as bear habitat (grey). Note that several potential bear habitats are geographically isolated and unlikely to become naturally recolonised.

Some 500 years ago, there were brown bears almost everywhere in Europe. However, in the following centuries they were wiped out in many places, including Germany. The reasons for the decline of bears were primarily habitat loss and hunting. Today, around 17,000 animals still live in Europe, distributed over ten populations and 22 countries. Some of these populations are at risk due to their relatively small size.

Excellent opportunity for species conservation

In recent years, the hunting of brown bears has been banned or restricted in Europe. In the future, bears could recolonise parts of Europe. A new study led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) reveals: there are still many areas in Europe where there are currently no bears, but which would, in principle, be suitable as habitat. Of an estimated amount of more than one million square kilometres of suitable habitat in Europe, about 37% is not populated; equivalent to an area of about 380,000 square kilometres. In Germany, there are 16,000 square kilometres of potential bear habitat. However, the probability of future recolonisation varies widely. E. g. in Germany, potential bear habitats outside the Alps are geographically isolated and unlikely for the bear to come back naturally.

“The fact that there is still suitable habitat for brown bears is a great opportunity for species conservation,” says the head of the study Dr Néstor Fernández from the iDiv research centre and the University of Halle. Scientists are already seeing around 70% of Europe’s populations recover, and it is likely that bears will return to some of the currently unoccupied areas. “In Germany, too, it is very likely that some areas will, sooner or later, be colonised by brown bears, especially in the Alpine region,” says Fernández. So, there is reason to hope that bears will be native to Germany once more, 200 years after their extermination.

Pre-emptive action important

For many people this would probably be good news. “In recent years, the attitude of Europeans towards wildlife has changed a lot. Today, many people feel positive about the return of large mammals,” says Fernández. Nevertheless, the fact that bear comeback can lead to conflicts with some human activities needs to be considered at an early stage. Such conflicts mostly arise when bears eat crops or damage beehives, and they also occasionally attack sheep. Direct attacks by bears on humans are, however, extremely rare; bears themselves generally steer clear of people.

The map developed by Fernández and his colleague Anne Scharf (Max Planck Institute for Ornithology) makes it possible to predict the areas into which bears could return. These maps can help policymakers identify potential areas of conflict early and counter these with specifically targeted measures. For example, compensation payments should be coupled with preventive measures being taken in advance, explains Fernández. Such preventive measures can be, for example, the construction of physical barriers such as closures for apiaries, electric fences, or the use of guard dogs to protect fields and grazing pastures, and increasing public awareness. A look at the map also makes it clear; bears do not stick to national borders. “That’s why a common management policy for the brown bear and other wild animals at the European level would be desirable,” says Fernández. At present, policies between member states regarding the protection and management of bears is very heterogeneous, and there is disparity in how compensation schemes are structured in different states.

Europe-wide map

For their study, Scharf and Fernández have collated the results of all relevant previous bear habitat studies. These each focused on a delimited area in which bears live, and, for this area, analysed which requirements the animals have for their habitat. By bringing together the results of these local studies, the scientists were able to create a computer model that would identify further potential bear habitat across Europe. The predictions made by this model are more reliable than if the data from one region were merely applied to the whole of Europe. Scharf and Fernández published their results in the journal Diversity and Distributions on 09 July 2018. Tabea Turrini

The brown bear

The brown bear (Ursus arctos) is one of the largest terrestrial mammals on Earth. Brown bears living in northern Europe weigh about 200 kg, southern European animals only about half that. Brown bears are omnivores, but feed mainly on plant foods. They eat, for example, fruits, beechnuts, grasses, insects and carrion as well as smaller mammals such as voles. They rarely prey on larger animals. Brown bears hibernate and are usually solitary, but cubs can stay with their mothers for about two years. Brown bears were originally distributed throughout Eurasia, North America and North Africa. Of the ten populations which still exist in Europe today, four are made up of more than 1,000 individuals, while three comprise fewer than 60; among these is the population in the Alps. The largest European population, with more than 7,000 animals, is in the Carpathians.

Original publication:

Anne K. Scharf und Néstor Fernández (2018): Up-scaling local-habitat models for large-scale conservation: Assessing suitable areas for the brown bear comeback in Europe. Diversity and Distributions. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12796

Contact:

Dr Volker Hahn

Media and Communications

German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv)

Phone.: +49 341 9733154

EMail: volker.hahn@idiv.de

Web: https://www.idiv.de/en/groups_and_people/employees/details/eshow/hahn_volker.html

Dr Néstor Fernández

Postdoctoral researcher

German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv)

Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg

Before: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Spain

Phone.: +49 341 9733229

EMail: nestor.fernandez@idiv.de

Web: https://www.idiv.de/en/groups_and_people/employees/details/eshow/fernandez_nestor.html

Note for the media: Use of the pictures provided by iDiv is permitted for reports related to this media release only, and under the condition that credit is given to the picture originator.